Nonprofit leaders who haven’t found the time to make their way through the 111-page nonprofit manifesto released by the National Association of Nonprofit Organizations & Executives (NANOE) will be forgiven. No worries, I am here for you. I present to you a high-level overview and a short review.

There has been some puzzlement and a lot of questions about emails that started showing up in the inboxes of thousands of nonprofit leaders across the country in July 2016, nominating them to be part of a Board of Governors whose sole task is to review and ratify a new set of guidelines for nonprofit practices. The full text of the Guidelines can be downloaded and reviewed here.

We believe that best practices call for boards to be more engaged, not less. Boards should be more diverse, not less. Boards should represent their communities as a whole, not just the elite…

Enter NANOE with a new set of guidelines for the nonprofit sector, designed, at least in part, to address the chronic under-resourcing of nonprofit organizations. Our assessment is that these guidelines are a mix of old news, ill-supported propositions, or suggestions downright contrary to best practices that could carry significant risks. They are written in an unwieldy, repetitive fashion that may make them impractical for use by nonprofit leaders and consultants that NANOE intends to certify, and also lack credible sourcing. I’ve provided an overview below that outlines the Guidelines based on three categories.

-

This is not news: Guidelines in this category are statements about good practices in the nonprofit sector that we can all agree with. For example, NANOE suggests that relationship building is critical.

-

Not enough info: Guidelines in this category may have some merit, but the detail contained in this text is not sufficient to fully vet them or, it is unclear whether a nonprofit would have the means or authority to implement these practices. For example, NANOE offers that donors should be a nonprofit’s primary customers.

-

Cause for concern: These practices directly contradict best practice and/or there is no practicable way to implement these practices sector-wide. For example, NANOE suggests that boards should have only four members and that board members be paid for their service.

This is Not News

If you’ve been around in the sector long enough, you have definitely run across a board of directors (or two, or ten…) that is running at less that optimum effectiveness. We’ve seen instances in which the board has too much authority and control, and we’ve seen instances in which the CEO has too much authority and control. This relationship is key to nonprofit success, but we often see it go wrong. Other statements used as the basis for the new Guidelines are not altogether wrong. Anyone who works in and with the nonprofit sector knows that relationships are key, that strong CEOs are needed, that nonprofits must work to diversify their sources of funding, and that the surest way to success is to commit some level of resources to building organizational capacity. Donors should be cultivated and engaged; programs should be evaluated for outcomes. We should be speaking out on behalf of the sector to lobby governments and funders to provide funding for indirect costs like infrastructure and administrative or fundraising overhead. These are basic points on which we can all agree. (NANOE Guidelines 1, 3, 9, 10, and 11, and parts of Guidelines 5 and 7).

Not Enough Info

Though we sometimes argue over what to call our sector, we have strong opinions about our purpose. We are here to make the world a better place through our efforts. We have always thought of our core mission and our primary customer as the people or causes to which we direct our resources. NANOE’s Guideline 4 recommends that we rethink this paradigm by adding donors and for-profit businesses as additional primary customers. I had to read very closely to find that the authors suggest them as an addition, rather than as a replacement for our mission. On page 56, the suggestion is that we rewrite our missions as such:

“Faith & Hope Food Bank provides donors, business partners, advocates & volunteers the organization they require to care for our community’s hurting, hungry & homeless.” , p. 56, Guidelines

I’m still thinking through the implications of this and weighing the pros and cons – as we all should consider what the result of this might be. I’d love to hear your thoughts, Tweet us @s4excel. One thought that immediately comes to mind is that it would fly in the face of the community empowerment movement whereby those being served play a stronger role in the governance and strategy of nonprofits that are active in their communities. (For some great examples of this, see the Building Movement Project.) Other guidelines I include in this category are things that nonprofits have little or no control over. Although there is a nugget of good thought here, these are not necessarily “guidelines” that nonprofits can implement. However, a nonprofit may be able to advocate for these ideas with their partners if it fits with their own mission and structure.

-

NANOE suggests that there should be directives to funders and for-profit partners to be actively engaged in decision-making at the organizations they fund. (NANOE Guideline 5) On one hand, this would give more power to the already powerful, but on the other hand, perhaps it could lead to more resources. This guideline is not fleshed out enough to get sense of the depth and breadth of engagement the authors suggest.

-

NANOE also offers directives to university faculty to exchange services with nonprofits: namely, assistance in securing large grants in return for using their clients as research. (NANOE Guideline 6). The faculty that I know already have a tough enough time raising funds for their research; it’s hard to imagine this truly scaling up. Not only that, but I’d like a whole lot more information about the research standards and funding rules that would accompany such a proposition.

Finally, in this category, I would add NANOE Guideline 9. (Build more social enterprises and consider whether your organization would be better off as a for-profit or benefit/L3C corporation.) I’ve seen very successful social enterprises, and I have seen social enterprises that have fizzled out within a few years. The same can be said of other resource development opportunities – fundraising from individuals, funds from foundations, government contracts, and fundraising from events. Social enterprise is no panacea, and it should be entered into with the same caution that any leader undertakes any significant change in strategic direction.

Cause for Concern

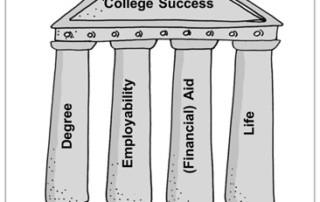

I’ve saved NANOE Guideline 2 for last. In my opinion, this is the crux of the suggestions that have the most capacity to do harm to our sector. Guideline 2 calls for repurposing the relationships between the CEO and boards of directors (and with donors and for-profit organizations, which I addressed above). There are two directives in this section which bring the greatest cause for concern.

The first directive is to restructure the board. NANOE suggest that we disband every board and reconvene it to include only four board members – an “enterprise development” specialist, a mission specialist, a CPA, and a lawyer. (Someone show me the queue where entrepreneurs, lawyers, and CPAs are waiting in line to serve on my board!) It is also suggested that most monitoring and planning activities, including regular financial and program oversight, should be stripped from the board. Fundraising is also dropped from the list of board responsibilities.

The NANOE Guidelines suggest that boards are to be used primarily in an advisory function, with a strong focus on ethics, legal compliance, and managing the CEO. In return, all board members are to receive compensation for their service. In a surprise addition, all board meeting minutes, including those not already subject to sunshine laws, are to be public documents.

The second directive is to give more authority to the CEO. NANOE suggests that the CEO act as the Chair of the board, set board agendas, and vote on board matters. Further, NANOE suggests that the CEO should have full authority to act on all organization matters and that the CEO is solely responsible for building relationships with stakeholders.

When it comes to organizational monitoring and oversight, the NANOE guidelines suggest that all nonprofits should be subject to an annual audit by an independent CPA. This replaces regular financial monitoring by the CEO and board. Additionally, all nonprofits should contract with outside bodies to complete program/organizational audits. This replaces regular program oversight by the CEO and board.

We believe that best practices call for boards to be more engaged, not less. Boards should be more diverse, not less. Boards should represent their communities as a whole, not just the elite, who, according to these guidelines, are to be provided an avenue to do good AND to do good for themselves AND to have an important seat at the decision making table. Further disconnecting nonprofits from the communities they serve will not lead to greater success.

Additionally, paying board members creates a self-serving interest on the part of the board member, and thus decreases their independence and objectivity. How will a paid board, essentially selected by the CEO, effectively and impartially provide the oversight to assure that basic governance standards of the IRS, and public service missions, be met? How would this group impartially review CEO performance and compensation? Granting the CEO authority to set agendas and vote on board matters could lead to a situation where these small, professional, and elite boards simply rubber stamp everything the CEO suggests. This has the potential to lead to a dangerously unbalanced relationship.

Suggesting the CEO hand over responsibility to manage the organization and the board hand over their oversight duties – to paid contractors – is not the solution that the nonprofit sector needs. Small nonprofits do not have the resources to meet this guideline, and nonprofits who could afford it should think carefully before passing these key responsibilities to outsiders.

Furthermore, the idea of having outside organizational consultants conduct regular audits to replace reporting is not practical and not good practice. A high quality organizational assessment can cost tens-of-thousands of dollars and is time consuming, with a time lag between assessment date and report-delivery. It is a good tool for periodic, strategic reviews by the board and CEO, but it is exceedingly expensive and could lack consistency, accuracy and timeliness for regular reporting that the board and CEO need to govern and manage the organization. One observer called these guidelines the “consultant full employment act!” We would rather see those resources going into the mission and infrastructure of the organization – and the individuals/community served.

The case for this NANOE’s Guideline 2, at least in this document, appears be built on anecdotal evidence from very large nonprofits. (Small nonprofits, which make up 2/3 of the nonprofit sector in this country, would be costed-out by many of these guidelines…perhaps NANOE is suggesting that these groups should scale up or give up?!) While we share the frustration that leads the initial argument (many board/CEO relationships are not working), we cannot sign-on to the solution suggested here.

Conclusion

If you’ve paid your $100 to be on the Board of Governors to review and ratify this document, we suggest that you carefully read these guidelines and make your own decisions about the veracity of their claims and conclusions. There are solutions out there, offered by the many standard-setting bodies mentioned above. Our own Standards for Excellence accreditation program has been supported by independent academic research. There is no shortcut to success – organizational capacity building, strong relationships, resource strategies, and board service are HARD WORK, and there’s no getting around it. Maryland Nonprofits and the Standards for Excellence Institute are here to help you with that hard work!

1 One exception to this consensus on best practices has been Charity Navigator and its highly popular website for donors to see ratings on charities based largely on the percentage they spend on overhead. We disagreed with the Charity Navigator rating approach because exceedingly low overhead undermines an organization’s ability to have sound management systems to ensure full ethics and accountability. The Charity Navigator star seems to be fading a bit as they finally signed on to a letter a couple of years ago stating overhead is not the most important thing, impact is, but they, like everyone else, have failed to find an easy way to measure a nonprofit’s impact.

Maryland Nonprofits and the Standards for Excellence Institute’s President & CEO, Heather Iliff, reached out to NANOE’s leadership to inform them of our intent to publish this post and invite a response. Read NANOE’s response here.

NANOE Guidelines Summary

Key: “Not news” in blue. “More info needed” in purple. “Cause for concern” in red.

-

Relationship building is critical: egalitarian, networked, engaged, reciprocal, and trusting relationships are the keys to success.

-

Re-Purpose Relationships between CEO, board, donors, and for-profit businesses

-

Restructure the board: Four board members only, to be used as “counsel” to the CEO (not as community members/owners of organization assets) – enterprise development specialist, mission specialist, CPA, and a lawyer. Strip most monitoring and planning activities, including regular financial and program oversight. Boards are not involved in fundraising. Emphasis on ethics, legal compliance, managing the CEO, and holding the CEO accountable for strategy and outcomes. All board meeting minutes are public. Board members are paid “at least” an honorarium.

-

Give more authority to the CEO (do NOT call them an Executive Director): They serve as Chair of the board set board agendas, and vote on board matters. CEO is granted full authority to act on all organization matters. CEOs should be freed to concentrate on building relationships, fundraising, and building the capacity of the organization, while program managers have broader authority andresponsibility over their program areas and strong development support is provided through a development office.

-

All nonprofits should be subject to an annual audit by an independent CPA (not the CPA on the board). This replaces regular financial monitoring by the board.

-

All nonprofits should contract with outside bodies (not named?) to complete program/organizational audits. This replaces regular program oversight by the board.

-

Donors and for-profit businesses are seen to be primary customers (See below, Guideline 4).

-

Strong CEOs build and maintain effective organizational and operational capacity, including strong external relations and strong human capital practices.

-

Re-define the mission statement to include two primary customers – donors and for-profit partners AND the community served. Rewrite mission statements such as, “Organization X provides a means for donors, advocates, volunteers to support a specific cause.”

-

For funders and for-profit partners: Be partners with nonprofit CEOs to build high performing organizations. CEO should spend considerable amount of time on building networks and partnerships and bringing funders into organizational decision-making processes.

-

Diversify fundraising sources, including social enterprise and capital investments. Also, apply for governments to fund indirect costs and partner with university faculty to grow revenue (faculty has access to clients and data for research, faculty assists in securing large dollar grants). (See also guidelines 7 and 9 below).

-

Raise capital for capacity building and grow and sustain change through the use of capital investments. Grow strategically based on a strong business plan. Report investment income separately from other revenue sources.

-

Identify and communicate infrastructure costs as necessary to accomplish mission. This guideline is about changing the public and donor perception of overhead.

-

Build social enterprises and consider re-incorporating (for instance, as a B-corp or L3C). (See Guideline 6 above).

-

CEO leads all fundraising efforts and is an effective fundraiser. Cultivation and stewardship of donors is a key function of the CEO (see Guideline 2 above). CEO may engage consultants, but must maintain accountability.

-

Engage in evaluation of the organization, its outcomes, and the effect of growing capacity on service delivery.